In the U.S., there are two types of meningococcal vaccines that may be given to children between the ages of 11-18 years of age: MenACWY and MenB. MenB is not yet routinely given or recommended in the US, and should only be offered if your child is considered to be at an increased risk (i.e. asplenia or persistent complement component deficiencies). For that reason, we will focus here on the MenACWY vaccine.

MENINGOCOCCAL DISEASE:

The MenACWY vaccine is typically administered once at age 11-12 and again at age 16 (two doses, total). There are currently three different brands of MenACWY vaccines licensed for use in the United States: Menactra (manufactured by Sanofi), MenQuadfi (Sanofi), and Menveo (GSK). (Package inserts are linked for each vaccine.)

Each vaccine insert states that MenACWY vaccines are “indicated for active immunization to prevent invasive meningococcal disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroups A, C, Y, and W-135″. (Emphasis mine.)

For clarification, from eziz.org, an educational website for California’s VFC (Vaccines for Children) program:

“Are there different types of meningococcal disease?

There are at least 12 types, called serogroups, of N. meningitidis. Serogroups B, C, and Y cause most of the infections in the United States. Serogroups A and W are more common in other parts of the world.”“What is meningococcal disease?

Meningococcal disease is a rare, but extremely dangerous illness caused by certain bacteria (Neisseria meningitidis). About 1 in 10 people have these bacteria in their noses or throats but are not ill. These people can spread the bacteria to others during close or lengthy contact, especially if living in the same household. Coughing, sneezing, kissing, and sharing drinks are all ways the bacteria can be spread.Those who become sick suffer from blood poisoning or meningitis, which is inflammation and swelling around the brain and spinal cord. Even when treated, meningococcal disease kills 1 out of 10 cases. Of those who survive, up to 1 in 5 will suffer long-term disabilities such as hearing loss, brain damage, loss of arms or legs, or severe scarring of the skin.”

The paragraph above likely sparks some concern, but let’s back up and dig a little deeper.

If you were to google search “meningococcal disease”, you’d easily find information similar to the above, along with sources claiming the meningococcal vaccine is responsible for the decline in incidence and therefore mortality of meningococcal disease.

But what is the actual evidence behind these claims?

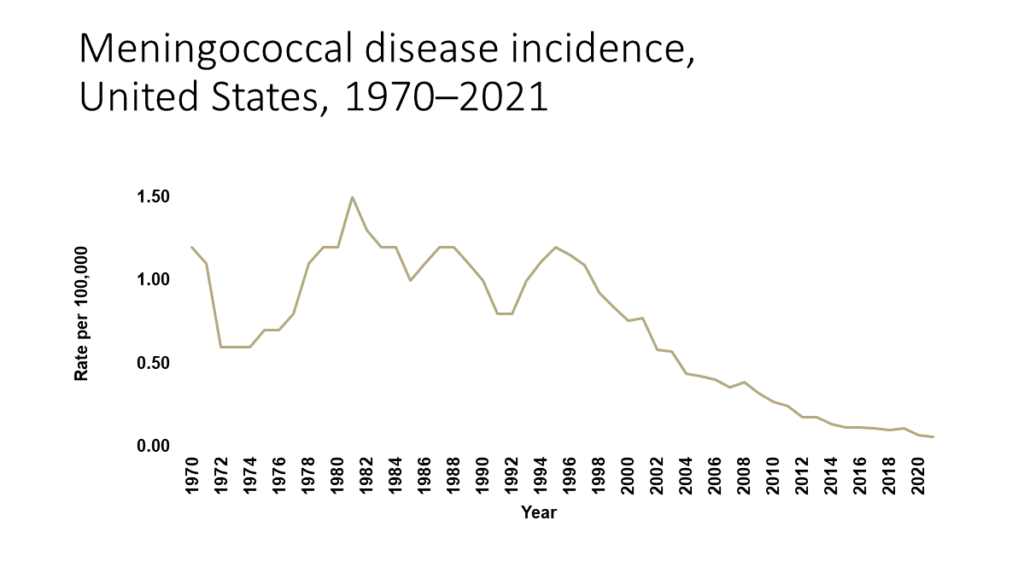

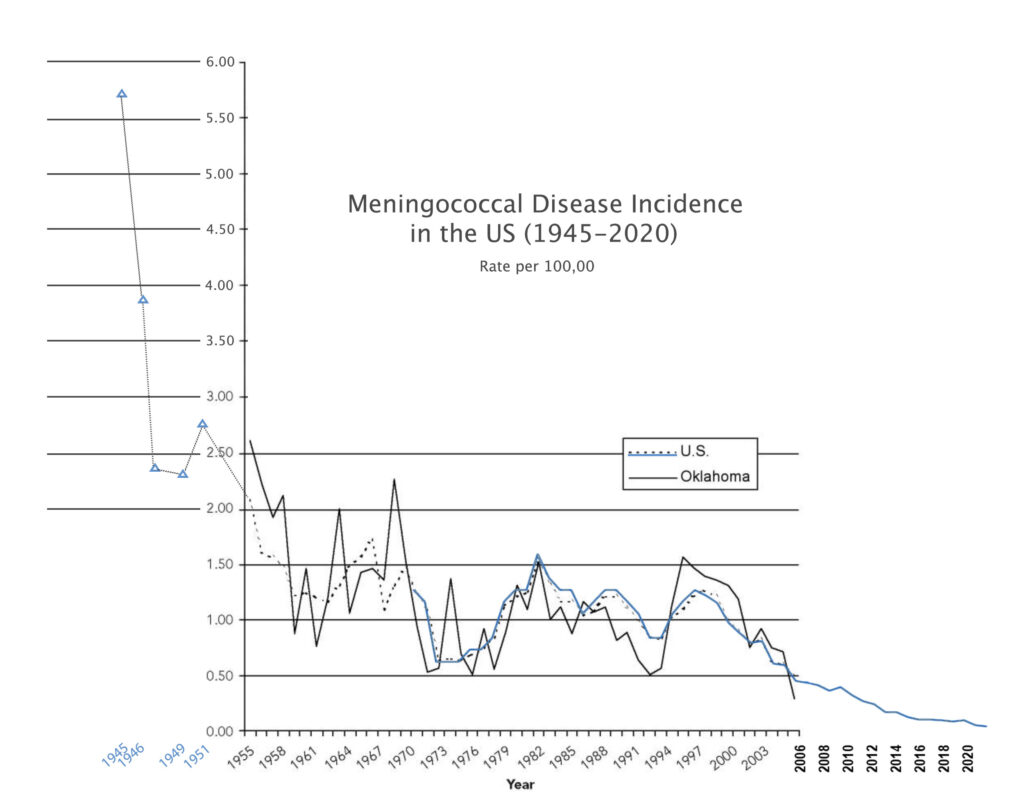

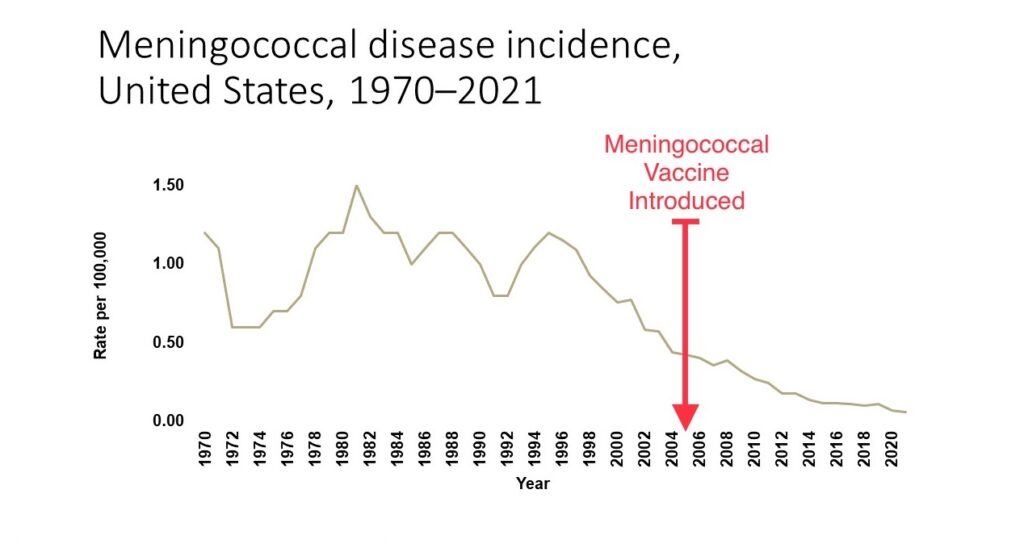

The CDC graph here presents the incidence of meningococcal disease in the US, per 100,000 population, starting in 1970.

In 2018, for example, there were less than 330 cases of meningococcal disease in the United States (population 326.8 million in 2018). That’s a 0.0001% chance of contracting meningococcal meningitis, or 1 case per 1 million people living in the US. There were a total of 39 deaths attributed to meningococcal disease in 2018.

Of course, some reading, are thinking: “But the vaccine is responsible for the decline in meningococcal disease, and that’s why the incidence is so low. If we didn’t vaccinate, more people would contract this disease and die from it.”

This is the rationale for every infectious disease for which, we have a vaccine. And that’s likely why the CDC’s graph of meningococcal disease incidence neither includes data prior to 1970, nor indicates when the meningococcal vaccines were first introduced (2005).

In 1970, the US population was 203.4 million and the incidence of meningococcal disease was 1.2 per 100,000 persons. Therefore, around 2,440 individuals out of 203.4 million contracted the infection, in 1970. According to the National Meningitis Association, 10-15% of individuals who contract meningococcal disease will die even with treatment. Using 15% as the death rate, there were up to 366 deaths in the US due to meningococcal disease, and the risk of dying of meningococcal disease in the US was around 1 in 555,000, in 1970. If 20% of meningococcal disease cases end up with long-term disabilities, that’s 488 individuals ending up with long-term disabilities from meningococcal disease.

366 deaths + 488 with long term disabilities = 854 individuals died or were permanently affected by meningococcal disease in 1970, three and a half decades before the vaccine was introduced (this rate is 0.4 per 100,000 persons). This means 99.99958% of the population was unaffected by meningococcal disease in 1970. Adding up that risk over an entire lifetime (75-80 years) at that rate (0.0042% per year), this means 0.03% of the population may die or be permanently injured by meningococcal disease over an 80-year time period based on the rate of harm, in 1970.

This is far, far less than influenza and other flu-like illnesses. To put this into perspective, in the year 2021, over 1200 women died in childbirth in the US (33 women for every 100,000 live births) and deaths due to choking was 1.6 per 100,000 population (vs 0.4 per 100,000 for meningococcal disease).

What about the data prior to 1970?

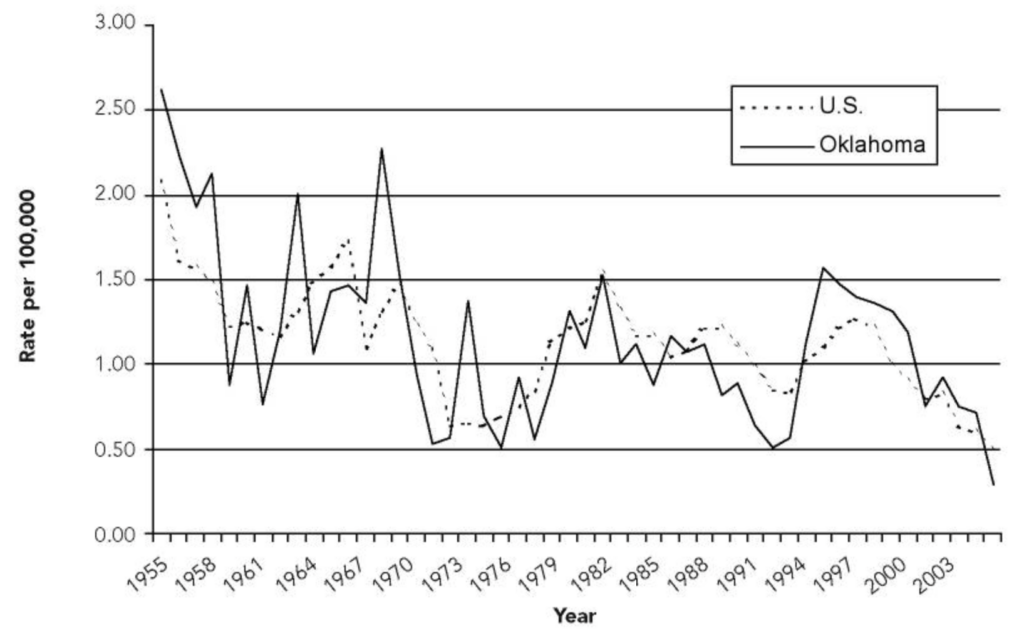

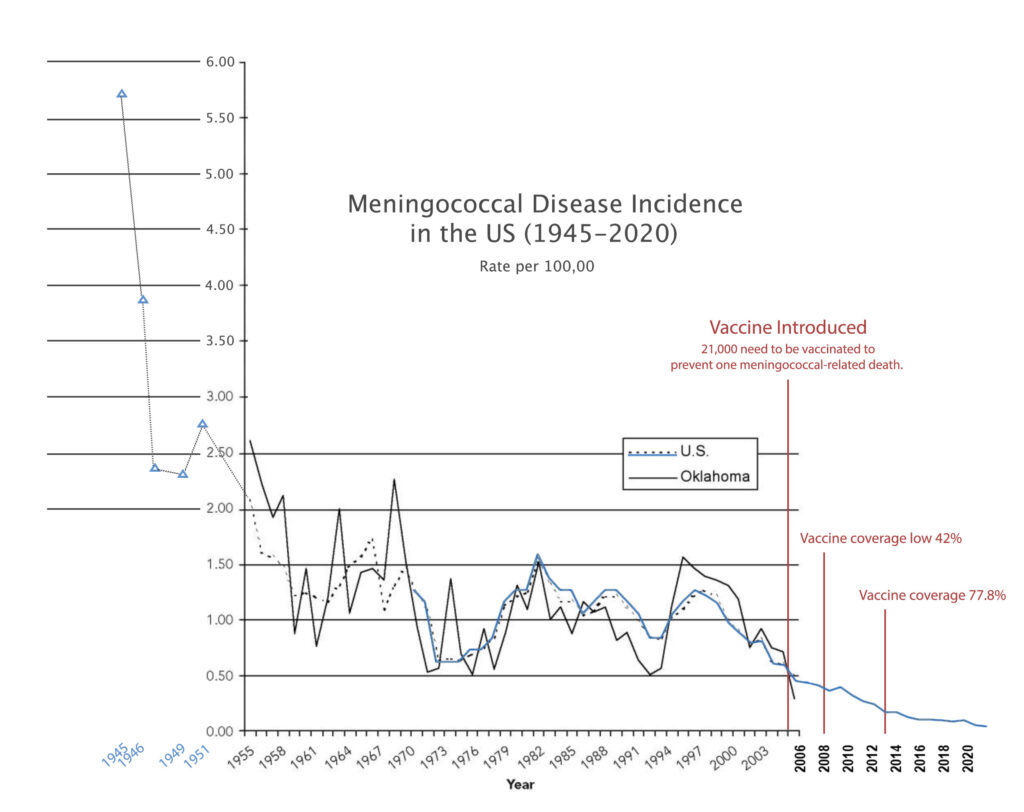

The graph below is taken from a published study on trends in meningococcal disease in Oklahoma and the United States, and presents incidence rates from 1955 to 2006.

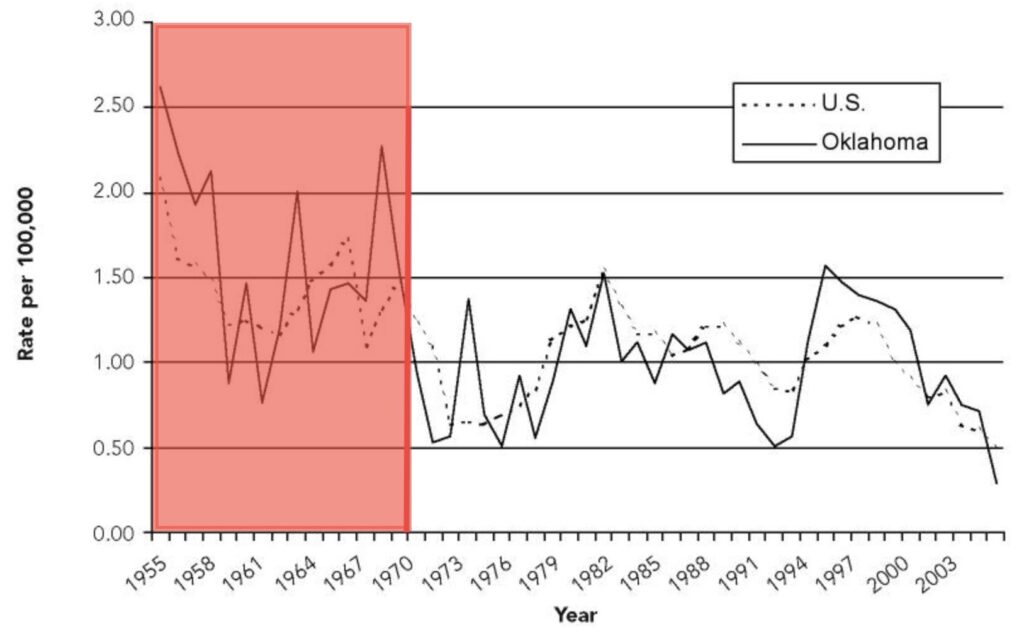

This graph looks much different than the one from the CDC website, primarily because of the years of data prior to 1970 that the CDC chose to exclude from their graph. The CDC’s graph starts with data from 1970, about half way down from a peak in incidence in 1969. (Additional data from 1955-1970 in red.)

Cutting the historical data off at 1970 is unfair to anyone trying to understand the overall trend in meningococcal disease incidence, because it makes the trend look relatively level until 2005, rather than seeing the longer term trend, which is a decline in incidence and magnitude of outbreaks:

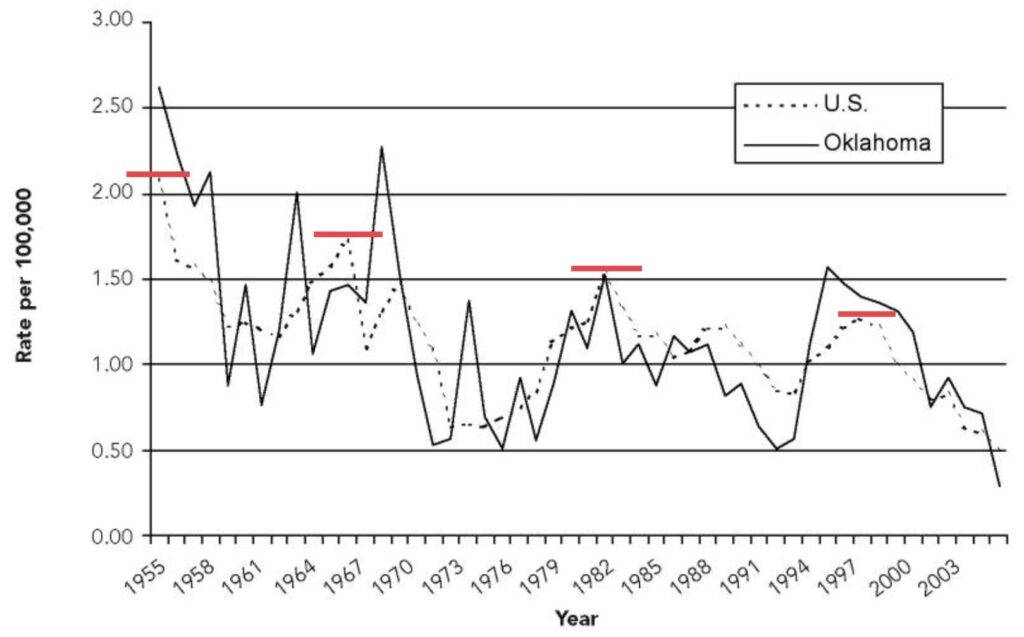

While the incidence of meningococcal disease has risen and fallen over the decades, it’s clear from the graph above that there has been a downward trend since 1955. Looking even further back, an article published in 1952 notes that the number of reported cases in the US per 100,000 population, was 2.7 in 1951. Therefore, peaks in incidence occurred in 1951, 1966, 1981, and 1997 (every 15-16 years). Thankfully, the same study also included incidence rates for earlier years. The graph below combines the two previous graphs, plus data points from the 1952 study.

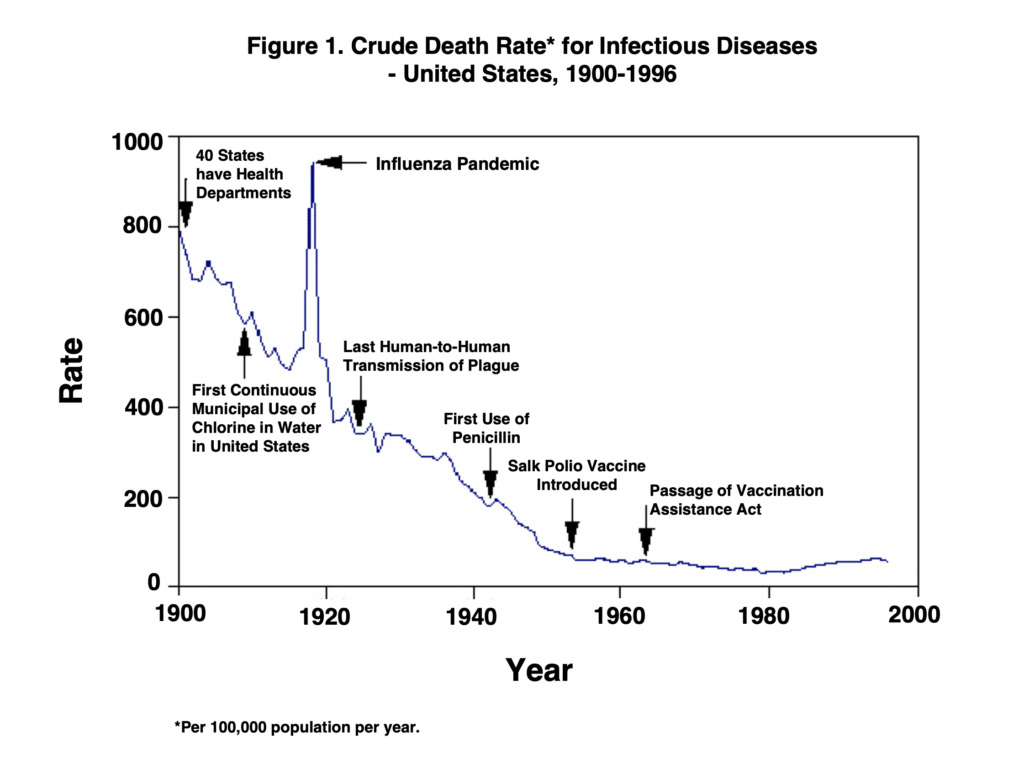

As you can see, the incidence of meningococcal disease has historically been quite high, and like many other infectious diseases, incidence (and therefore mortality) declined dramatically along with improvements in nutrition, sanitation, hygiene, disinfecting water sources, etc. prior to the introduction of nearly all vaccines in use today. More on the decline in infectious diseases and necessity of vaccination, here.

Of course, this information doesn’t prevent government regulatory agencies and other organizations from continuing to claim that vaccines are responsible for saving us from dying of infectious diseases.

From the National Meningitis Association: “Historically, the number of meningococcal disease cases went up and down over time. Now, the number of cases is at the lowest it has ever been. Health officials believe this is due, in part, to the increased use of meningococcal vaccines.”

Now that we’ve seen the historical data, this statement really side-steps a lot of important information, doesn’t it?

So, how much of an impact did the meningococcal vaccine actually have on the decline in meningococcal disease?

Can we know?

THE MENINGOCOCCAL VACCINE:

The meningococcal vaccines were introduced in the US, in 2005. By looking at the CDC graph only, and seeing when the vaccine was introduced relative to the historical data, trends, and decline in incidence, one could argue that the statement from the National Meningitis Association appears to be accurate. But again, there are finer details being missed here, that are important to know.

While the MenACWY vaccine was introduced in 2005, vaccination coverage was only at 12% in 2006. By 2008, coverage in the US was at 42%, and by 2013, this went up to 77.8%. In general, vaccination is not typically considered to impact a population (help prevent outbreaks) or provide herd immunity until coverage (the percentage of the target population vaccinated) reaches 80% or more. This is the case for polio (80%), but for measles, it’s said that in order to maintain herd immunity, 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated (or have natural immunity). It’s not always known exactly what level of vaccination coverage is required to prevent transmission or reduce incidence of any particular disease in a population.

In addition, “[in order] to prevent 1 meningococcal-related death, [it’s been] estimated that about 21,000 people would need to be vaccinated“. Read that again. Nearly 21,000 people need to be vaccinated in order to prevent one person from dying of meningococcal disease. This is known as the “NNT” or Number Needed to Treat (or in this case, the number needed to vaccinate, or NNV). It’s necessary to include that this estimation is based on the assumption that the vaccine is 100% effective against types A, C, Y and W135, which, it is not. No vaccine is 100% effective, not even close, despite claims.

For example, the CDC claims that protection against measles is 97% with two doses of the MMR vaccine… (One of the most “effective” vaccines that exists.) Yet, they don’t include exactly how long you’re “protected” for. After 10-15 years, antibodies that the immune system may have originally produced, wane or drop to levels that are considered “below protective”, and based on research, we know that a third dose does not help.

For the meningococcal vaccine, the reason the CDC recommends a second dose at age 16, is because antibodies wane to below protective levels 5 years after the first dose. The CDC goes on to say, “The booster dose provides protection during the years when they are at highest risk of meningococcal disease.” (Emphasis mine.) On the same page, the CDC states that, “adolescents and young adults 16 through 23 years of age are at increased risk for meningococcal disease”.

So what does that mean? Essentially, any “protection” from the vaccine is short-lived. One study published in 2017 states that the meningococcal vaccine “was effective in the first year after vaccination but effectiveness waned 3 to <8 years postvaccination”. Therefore, although the CDC avoids making a clear statement on the duration of protection, this research supports the fact that there is no longer any protection against meningococcal disease after 23 years of age, despite taking two doses as recommended.

I will let the reader decide whether or not the information above demonstrates that the vaccine is effective.

Let’s move on to…

SAFETY:

What do we know about the safety of the MenACWY vaccines? If they’re safe, then what’s the harm in taking the shot if it could potentially help save someone’s life, even if effectiveness is low?

Let’s check the VAERS database on the HHS website for adverse events. (VAERS = Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System.)

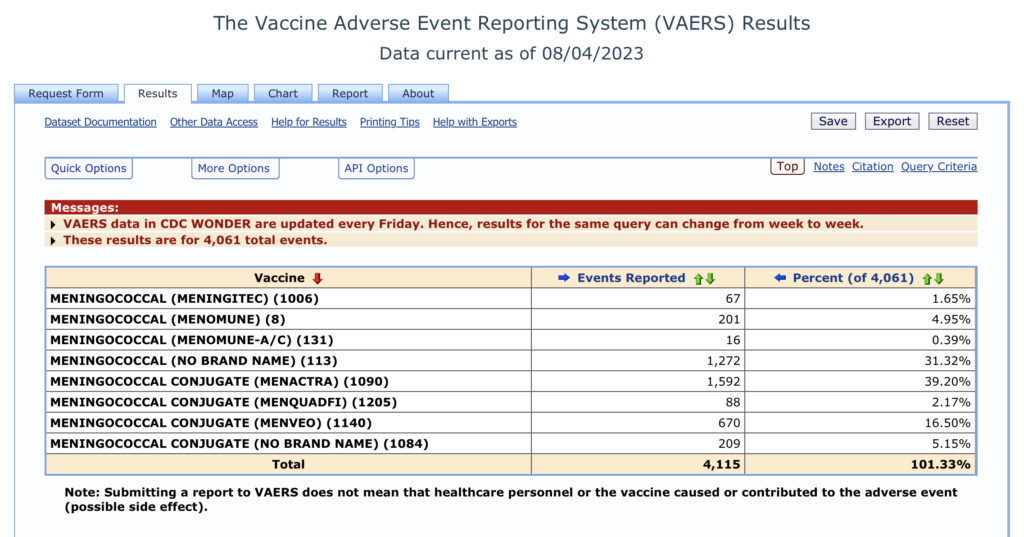

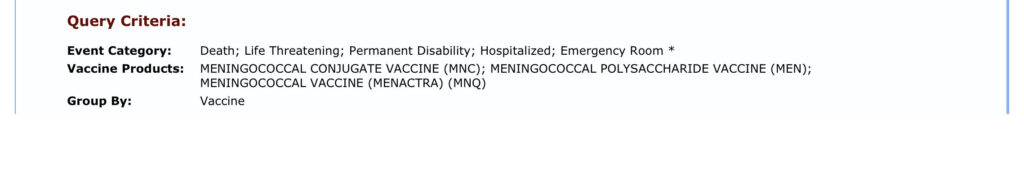

Selecting for MenACWY vaccines, I searched for reports categorized as life threatening, hospitalized, emergency room visits, permanent disability, or death:

From 2005 – 2023, there have been 4,061 adverse events reported to VAERS that were categorized as life threatening, hospitalized, emergency room visits, permanent disability, or death.

It is critical to note, that according to an HHS-funded VAERS study, fewer than 1% of adverse events from vaccines are reported to VAERS. Considering this underreporting factor, the 4,061 adverse events listed in the results from my query above (red text), represent at least 406,100 adverse events.

I then searched the database for deaths only. When considering the underreporting factor, there have potentially been over 18,500 deaths from meningococcal vaccines since they were introduced.

Now that we have this information, what poses the greater risk? Meningococcal disease? or the Meningococcal Vaccines?

Let’s compare the number of deaths from meningococcal disease, using incidence from 2004 (just before the vaccine was introduced), to the number of deaths indicated by the VAERS database (18,500), since the vaccine was introduced in 2005.

If VAERS indicates that there were 18,500 deaths since 2005, then 18,500 deaths divided by the 18 years since the vaccine was introduced = 1,028 deaths following the meningococcal vaccine, each year.

In 2004, the incidence of meningococcal disease was 0.44 per 100,000. Population in 2004 was 292.8 million. Number of cases in 2004, therefore, was 1,288. Using the high end of the death rate, at 15%, 193 people died of meningococcal disease in 2004.

What does this mean?

Based on the CDC’s own data, from their own website, and the HHS-funded VAERS study, MenACWY vaccines are ending the lives of over five times as many people as meningococcal disease itself.

Again, there are five times as many deaths following the meningococcal vaccine, each year, than from meningococcal disease itself.

It appears that parents who’ve gotten their child the first dose of the meningococcal vaccine may be realizing that the risk of harm from the vaccine, is not worth it, as well. The National Meningitis Association states that, “Less than one-third of first dose recipients have received the recommended booster dose.”

This could be an indicator that some parents and teens are declining the second dose due to adverse events from the first.

At 18 years old, Haleigh received the meningococcal vaccine. She was about to start college and her pediatrician highly recommended she take the vaccine in order to protect her from the disease while living on campus. After the vaccine, Haleigh began having seizures. By the end of her first semester, she was diagnosed with epilepsy. She endured tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures for two years and unexpectedly passed away at the age of 20, in 2018.

Haleigh’s life was tragically cut short, because of a vaccine that was supposed to protect her.

Haleigh’s parents were not informed by medical professionals of the risk that their daughter could develop seizures and eventually lose her life, when consenting to the meningococcal vaccine.

All drugs come with side effects. It is critical to know what you’re consenting to when you take any medication or vaccine. Yet the vast majority of parents are not made aware of the many potential adverse events that can occur when their child is vaccinated.

The vaccine package inserts list the following adverse events which have been reported to occur following administration of the meningococcal vaccines (from the Menactra and Menveo inserts):

– Lymphadenopathy.

– Hearing impaired, ear pain, vertigo, vestibular disorder.

– Eyelid ptosis.

– Large injection site reactions, extensive swelling of the injected limb (may be associated with erythema, warmth, tenderness or pain at the injection site). Injection site pruritus; pain; erythema; inflammation; fatigue; malaise; pyrexia.

– Hypersensitivity reactions such as anaphylaxis/anaphylactic reaction, wheezing, difficulty breathing, upper airway swelling, urticaria, erythema, pruritus, hypotension.

– Vaccination site cellulitis.

– Fall, head injury.

– Alanine aminotransferase increased, body temperature increased.

– Arthralgia, myalgia, bone pain.

– Guillain-Barré syndrome, paraesthesia, vasovagal syncope, dizziness, facial palsy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, transverse myelitis.

– Dizziness, syncope, tonic convulsion, headache, facial paresis, balance disorder.

– Oropharyngeal pain.

– Skin exfoliation.

Note that “tonic convulsion” (tonic-clonic / grand mal seizure) is listed above. Encephalomyelitis and transverse myelitis are also listed, which are inflammation of the brain and/or spinal cord. Both of these conditions can cause seizures.

More information about Haleigh, her story, and additional resources, are available here.

For information on vaccine exemptions for your state, please go to NVIC.org.

CONCLUSION:

While the perpetual stance by the CDC and news media is that vaccines are safe and effective, and that any harm inflicted by vaccines is not only exceedingly rare, but that benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks, the data and evidence do not support these claims.

From the historical data, we can see that the incidence of meningococcal disease declined dramatically to very low levels, prior to the introduction of the vaccine. In addition to this, it’s difficult to ascertain whether the vaccines had much of an impact at all, on meningococcal disease incidence. Finally, the vaccine may be ending the lives of five times as many people as meningococcal disease itself.

Please reconsider vaccinating your child, and please share this information with others.

Additional References:

The Potential of Melatonin in the Prevention and Treatment of Bacterial Meningitis Disease

Adolescent Vaccination-Coverage Levels in the United States: 2006 –2009 | Stokley, S., Cohn, A., Dorell, C., Hariri, S., Yankey, D., Messonnier, N., & Wortley, P. M. (2011). Adolescent Vaccination-Coverage Levels in the United States: 2006-2009. PEDIATRICS, 128(6), 1078–1086. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1048